There’s something different about Season 3 of BBC’s Sherlock. Have you noticed?

Sherlock’s getting nicer.

No, he’s still not exactly the cuddliest guy you’ll ever meet. In the most recent episode to air on PBS, he still described himself as a “high-functioning sociopath.” But he’s hardly the cruel, emotionless robot we’ve come to know in Seasons 1 and 2, during which he was horrible to pretty much everyone around him: his clients, Lestrade, Mrs. Hudson, Watson, but especially Molly, the morgue worker with an unfortunate crush on the unfeeling detective.

That’s all changed this season. In the past two episodes, we’ve seen Sherlock (SPOILER ALERT!):

1. Kindly invite Molly to accompany him on cases

2. Try to make Watson forgive him after faking his own death

3. Shame his brother Mycroft for having no real friends, implying that Sherlock really values his

4. Make nice with Watson’s fiance, Mary Morstan

5. Get goofy with Watson at his bachelor party pub crawl

6. Write a beautiful (if slightly unwieldy) best man’s toast that brings the entire room to tears

In short, the detective is evolving—as is the show, which has taken a more playful tone in the episodes I’ve seen so far. It’s practically become a sitcom, with the mystery plot taking a backseat to storylines with more emotional stakes: Sherlock returning to his old life to find that Watson’s moved on, or Sherlock’s attempts to make Watson’s bachelor party and wedding day memorable.

Not every fan may be excited about this change to the character or the feel of the show, but Sherlock’s evolution—his domestication, you might say—is following a well-worn path that mirrors that of the original Conan Doyle stories. By slowly evolving Sherlock—both the show and the character—from something dark and prickly to something lighter and kinder, show creators Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss are actually mimicking what Arthur Conan Doyle himself did with the character.

Sherlock Holmes first appeared in 1887’s A Study in Scarlet and 1890’s The Sign of Four. In those two novels, Holmes was presented to the audience as an odd and almost dangerous character. Watson catalogues Sherlock’s peculiarities almost as if he’s a freakish species of bug: he possesses deep knowledge about the things that help him with his cases, but knows nothing about politics, culture, and is unaware until Watson tells him that the earth revolves around the sun. He plays the violin beautifully but prefers to simply drag the bow across the string, making unearthly sounds that I imagine might have anticipated the thoroughly modern noise that Igor Stravinsky would foist on the world a few decades hence. And he takes morphine and cocaine intravenously, a habit detailed in the opening scene of The Sign of Four. In pretty much every way imaginable, the Sherlock of Doyle’s early stories defied Victorian notions of what an upstanding British gentleman should be: well-rounded, acquainted with life’s finer things, polite, and above all in control of his vices.

Most threatening of all, though, is his freakish knack for detection—his seemingly supernatural ability to just know things. It’s a useful skill, of course, but it’s entirely undifferentiated: Sherlock could just as easily use his powers of detection and deduction for ill as he could for good. Society—particularly Victorian society—depends upon secrecy in some contexts: it’s not always proper to speak the unvarnished truth in polite company. So, when Sherlock—moments after shooting up in The Sign of Four—deduces a painful family secret just by looking at a pocketwatch belonging to Watson’s brother, it’s a reminder that though the detective is extraordinarily powerful, his power is not necessarily good.

Detectives are so ubiquitous in books, TV, and movies today it’s easy to forget that in Conan Doyle’s day, detectives were still relatively new to society—and audiences hadn’t quite decided what they thought of them. The British public in the late 1800s was simultaneously hopeful and fearful: hopeful that detectives might help solve the ever-growing problem of urban poverty, but fearful that a cadre of policeman with Holmes-like powers might invade their privacy and expose things they might prefer to be secret. Some even worried that detectives, in their proximity to the criminal underworld, might become criminals themselves.

In this context, Sherlock and Watson’s relationship in the early stories is almost that of a trained dog and its master: Holmes is very good at doing one thing, but he needs Watson around to keep him on a leash and make sure that the detective uses his powers appropriately.

However, just as in Moffat and Gatiss’s Sherlock, that’s something that changes over time. In the Conan Doyle short stories, Sherlock’s behavior becomes less eccentric and more mainstream. His drug habit recedes to the background. By the time Conan Doyle wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles, Sherlock was basically a fully domesticated English gentleman. Contrast the closing of The Sign of Four with that of Baskervilles: in the former, we leave the detective reaching toward a syringe full of cocaine; in the latter, the book ends with Holmes inviting Watson to share his box seats at the opera.

The domestication of Sherlock Holmes plays a little differently now than it did in fin de siecle Britain. Though we still have the trope of the damaged detective who struggles to fit in the human communities that he or she protects, we have no real anxieties about the place of detectives in society. The domestication of Sherlock in Moffat and Gatiss’s Sherlock is more related to the modern phenomenon of the “bromance.”

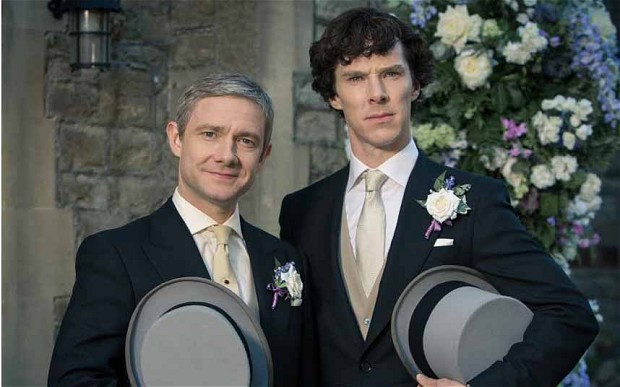

There’s a recurring joke in the show where people mistake Sherlock and Watson for gay partners—a joke that reached a crescendo in this seasons “The Empty Hearse” when Watson told Mrs. Hudson he was getting married and she asked, “Who is he?” Sherlock and Watson aren’t homosexual—their bond is more properly homosocial. Yet their relationship has functioned a lot like a marriage.

Their bromance has, quite literally, domesticated Sherlock. Watson’s presence—his constant reminders of what is and is not appropriate behavior—have changed the detective in three short seasons, from a detecting, deducing circus freak unfit for polite society to a paragon of male camaraderie: a high-functioning sociopath who’s nevertheless capable of expressing genuine emotion.

And throwing a pretty damn good bachelor party.