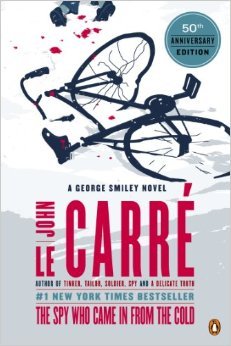

John LeCarre is the undisputed master of the spy novel, and 1963’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is his most important novel. The book tells the story of Alex Leamas, a Berlin spymaster working for the British Intelligence Service—called “The Circus” by agents in the field. Leamas’s agents in East Berlin have been dying, killed by a former Nazi turned Communist named Mundt, and in the book’s opening scene, Leamas’s last agent dies in an attempt to flee to West Berlin. His network completely blown, Leamas returns to London in disgrace, where he is recruited by Control, the head of the Circus, for one last job: Leamas must go back into “the cold” to bring Mundt down and exact his revenge.

John LeCarre is the undisputed master of the spy novel, and 1963’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is his most important novel. The book tells the story of Alex Leamas, a Berlin spymaster working for the British Intelligence Service—called “The Circus” by agents in the field. Leamas’s agents in East Berlin have been dying, killed by a former Nazi turned Communist named Mundt, and in the book’s opening scene, Leamas’s last agent dies in an attempt to flee to West Berlin. His network completely blown, Leamas returns to London in disgrace, where he is recruited by Control, the head of the Circus, for one last job: Leamas must go back into “the cold” to bring Mundt down and exact his revenge.

It’s a setup worthy of a great crime novel—and indeed, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold bears more than a passing resemblance to a hardboiled Dashiell Hammett novel, from the intricate plot that keeps revealing layers right down to the last chapter to the nihilist antihero at the book’s center, just trying to keep his head and keep alive in a morally bankrupt world where everyone’s working an angle. LeCarre, throughout his career, specialized in male protagnists who had been hollowed out morally and ethically by the spy game. Alex Leamas is probably the most uncompromising example of this—the least likable and least charismatic character of any LeCarre novel.

This isn’t a critique of the book. On the contrary, Leamas’s psychological and spiritual deformity—the sense one gets that after so many years in the spy game Leamas has simply forgotten how to be a person—is one of the best features of the book, and a key to LeCarre’s critique of Cold War politics. This is no Bond novel; in LeCarre’s world, being a spy is not glamorous. After years playing the spy game, Leamas has become a moral grotesque. A woman asks him if he loves her and he says he doesn’t “believe in fairy tales”; later, a Communist asks him what his philosophy is and Leamas replies, “I just think the whole lot of you are bastards.” He believes in nothing except revenge.

As for the plot—well, I hesitate to reveal too much of it to you. LeCarre deliberately withholds the details of the Circus’s plot against Mundt from the reader, and observing how the plan unfolds and goes awry as it happens is one of the great pleasures of the book. Suffice it to say that it’s full of double- and even triple-agents, and it’s hard to tell which is which and what side everyone’s on until the very end.

I’ve long had a theory about John LeCarre novels that much of their tone and character comes from the atmosphere of English boys’ schools—that the spy game played in the Circus is an extension of the sports and social climbing and academic competition that British boys of a certain class experienced in boarding school. There’s a connection between the casual scheming and betrayal of John Knowles’ A Separate Peace and the intricate spycraft of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold or Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. LeCarre’s spymasters are still just boys—the only difference is that now they’re playing with the fate of nations and human lives.

This, ultimately, is the bleak vision of the book: a world in which both sides, British and Communists, play games with people’s lives: with their allegiances and their affections, and with the weakness of their bodies, so easy to kill or torture. Sacrificing the one for the many. As Leamas says near the book’s close:

What do you think spies are: priests, saints, and martyrs? They’re a squalid procession of vain fools, traitors too, yes; pansies, sadists, and drunkards, people who play cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten lives. Do you think they sit like monks in London balancing the rights and wrongs?

This is Leamas, remember: a man who believes in nothing except revenge, who thinks that love is a fairy tale.

And yet I wonder. I reread the book recently, and something struck me about the ending. I won’t reveal it here, except to say that the plot moves to a conclusion that is both shocking and inevitable—and that Leamas makes a choice in the book’s final pages, a choice whose meaning is ultimately unclear. Is Leamas’s choice a final act of nihilism, or a triumph of sorts—a final stand for fairy tales, in defiance against the cynicism of power and violence?

Days after finishing the book, I still don’t know. But with trouble in the news, violence and ugliness and abuse of power at home and abroad, the answer seems to matter, just as much as it did in 1963.

Follow The Stake on Twitter and Facebook